“The reigning economic system is a vicious cycle of isolation. Its technologies are based on isolation, and they contribute to that same isolation. From automobiles to television, the goods that the spectacular system chooses to produce also serve it as weapons for constantly reinforcing the conditions that engender “lonely crowds.” With ever-increasing concreteness the spectacle recreates its own presuppositions.”

– Guy Debord (1967), The Society of the Spectacle

Last Wednesday I attended the second in a series of three lectures by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, the authors of The Spirit Level, hosted at the University of Auckland as part of the annual Sir Robert Douglas lecture series.

For those that haven’t read The Spirit Level, its central thesis is very simple. As income disparity increases, so do a wide range of health and social problems: violence, suicide, child abuse, obesity, depression – the list of negative outcomes associated with the degree of economic inequality is staggering, and as the lecture on Wednesday established, far more than just conjecture.

Richard began his talk by dismissing a classic rebuttal often raised when their correlations are first present – that of reverse causality. Not only do they now have empirically demonstrated examples where causality has been determined, but for many of the negative outcomes, logic denies reverse causality. It would be a strange world indeed where factors such as higher death rates produced the burgeoning inequality we see today. Richard was also quick to point out that it’s not inequality on a neighbourhood scale that their research reflects, but the inequality within the whole of society. This is a collective problem, and requires collective effort to address it.

Inequality and its negative outcomes are linked to the overall structure of class and the importance of status within society. In a nutshell, bigger material differences create bigger social distances, and increase social class differentiation. As wage and wealth inequality increase, our societies become more hierarchical. Class becomes more important, and with it, the narratives of superiority and inferiority used to justify and reinforce it. Material differences provide the framework on which the cultural markers of status and class differentiation develop, and the more pronounced these differences are, the less we feel connected – and the more the quality of our social relations is impacted. While class was originally thought to just be a proxy for the real cause, it is now seen as a central element.

Richard pointed out that when you consider the psychosocial risk factors for ill health – low social status, weak social connections, stress in early life (pre and post-natally) – they all point to one underlying sort of stress: the fear of not being valued, of being worthless.

Respect: a demonstration of value. (Picture credit: HONY).

This is a claim supported by Dickerson and Kemeny’s (2004) meta-analysis of studies measuring the stress responses of participants across different activities. Tasks with social evaluative threat, that is, where there is a risk you will be seen and judged, produced far greater levels of cortisol (the hormone released when stressed) than other tasks lacking this interpersonal dimension. This is corroborated by another study demonstrating that the more you feel shamed, the more it affects your psychological wellbeing. Even low levels of stress raise death rates – it isn’t difficulty that makes us worry per se (and by extension, commence the physiological processes that lead to negative health), but what others might think.

This sensitivity to status doesn’t just affect our physical health, but also our cognitive performance. Work by Hoff and Pandey (2004) demonstrates this – with Indian children made aware of their caste status performing to the expected levels, in stark contrast to their performance in absence of this status being salient. This phenomena is broadly known as stereotype threat, and has been proven over countless studies, from the effects of gender salience on maths ability to the association between race and competence when told that a specific test “measures ability”. When our class or ‘type’ is pointed out, we are quick to conform.

Across all this work Richard distils two poles: that of social status, and that of friendship. Social status refers to pecking orders and dominance hierarchies – and is based on power, coercion, and privileged access to resources regardless of the needs of others. In contrast, friendship is built upon reciprocity, mutuality, social obligations, sharing and a recognition of each other’s needs. Richard’s point is that it is this duality that is close to the heart of what we‘re discussing when we talk about inequality.

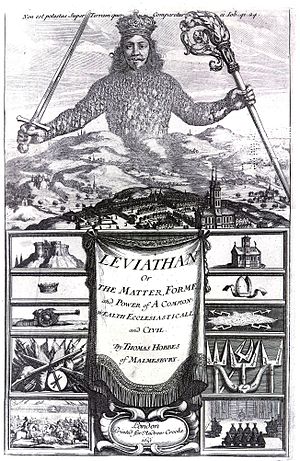

While Hobbes’ argument that society needs a controller has some resonance, Richard emphasises that this perspective fails to acknowledge the importance of friendship. We are not just rivals, but equally have the capacity for great collaboration: “we can equally be the worst or best for each other”. What remains, is our choice which to favour.

With friendship, this begins with a gift – providing the basic source of the social compact: something offered without expectation of return. From this, Richard explains, we see the significance of ritualised sharing: the breaking of bread. This is a significance reflected in our etymology: companion comes from French, copain, from the Latin con (with) and pan (bread). As Marshall Sahlins writes: “gifts make friends and friends make gifts” – if we are to contrast the evident pole of social hierarchy, our first step must be selflessness.

Richard moved on to a discussion of the effect of the ubiquity of dominance, citing a study where monkeys who had previous been solitary were then housed socially and the effects of the emergent dominance hierarchy on the brain studied. Those lower in the hierarchy had less dopaminergic activity (dopamine is a neurotransmitter associated with the reward circuit, and is central to our feelings of worth), and consequently took more cocaine than those categorised as dominant. That is, their social positioning affected their neurological activity, and the behaviour that they chose to persue. A similar physiological outcome occurs in humans, with lower ranked civil servants demonstrated to have more fibrinogen in their blood than higher ranked employees. Higher levels of fibrinogen are associated with higher levels of cortisol (stress) and produce an increased clotting response – a throwback to the days where stress was associated with physical harm.

Richard ended his half of the talk with a brief discussion on how inequality still produces this physical harm. In more unequal countries there are higher rates of bullying amongst children. While not all of this is violent, the status anxiety produced by gross inequality creates a sensitivity to being “demoted” – a sensitivity to disrespect and a loss of face that acts as a trigger for violence: the exertion of dominance over neighbours. This echoes the findings of Robert Sapolsky, whose work on baboon hierarchies concludes that “fights (trials of strength, social comparisons) tend to be between neighbours in the ranking system”. We don’t fight those so removed as to not even consider themselves our equals, those whose presence creates our anxiety – but instead we fight those who judge us based on that scale, those who are closest to us, and whose opinions we value most highly. This is the insidious nature of inequality; it pits the oppressed against the oppressed.

In the second half of the lecture Kate Pickett focused on the different ways that we respond to these stressors. She pointed out that we don’t just share genes with animals but also behavioural systems – for example, the dominance submission system (DSS).

The DSS is about how we get control over the things we want: social and material resources. Ultimately it’s about power, and whether we use dominance or submission to get it. Everyone uses a mixture of the two, with our experiences as developing children providing a working model for the balance that we favour, and the circumstances when we choose to utilise cooperation (submission) over competition (dominance).

Dominance behaviours and traits are linked more to externalising disorders such as narcissism, while submission is more related to internalising disorders, such as anxiety and depression. The increased emphasis on power in more unequal societies increases the extent to which we need to get it, and the extent to which we pursue it – explaining why more unequal societies have higher rates of mental illness. When we feel anxious, we have two choices: we can go under, and submit to helplessness (depression), or we can try and claw up by exerting dominance (violence, schizophrenia).

The outcome of this behaviour system is reflected in a phenomenon called the above average effect – for example, 93% of Americans think that they are better drivers than average. The above average effect is correlated with income inequality. In more unequal countries there is greater emphasis on status, and with it the need for self-enhancement and its corollary: narcissism.

Pickett talked about how both narcissism and self esteem are rising in the USA, but that this measure of self esteem fails to distinguish between a real assessment of the individual’s capabilities and their acceptance of them, and the narcissistic tendency to think you are better than you are. When these are pulled apart it becomes apparent that narcissism is rising over time, in direct step with income inequality. In this sense, narcissism can be seen as a natural response to the increased status anxiety of more hierarchical societies.

However with narcissism comes a whole host of other negative outcomes. People in more equal societies aren’t only less narcissistic; they are more happy, more agreeable, feel a greater sense of solidarity, have lower rates of depression and schizophrenia, and higher rates of civic and cultural participation – as if they feel that society is there for them, that they are welcome and consequently can take part in its construction.

This science sits in stark contrast to the political rhetoric popularised at the moment and its narratives of the poor as negative, and the rich as virtuous. Indeed, recent studies demonstrate that not only are people of high social status more likely to engage in unethical behaviours (both in and out of laboratory settings) – less likely to help someone in distress, more likely to cut other cars off and not stop for pedestrians, more likely to cheat – but that these people are more likely to admit that this is what they would do. What does this tell us? That power has a dehumanizing effect; that money really is an isolator – and that inequality is negative for all of us.

However, these aren’t fixed outcomes. In the experimental condition where those in the high social status group were given an egalitarian primer – that is, where they were asked to write a sentence explaining why all people should be treated equally prior to the experiment – the differences between the two groups decreased dramatically. This is the value of us talking about equality – it starts to change the way people think, and this in turn produces behavioural change.

Pickett points out that the effects of inequality involve two stages. First comes the adult experience of a more unequal society, with this informing parenting style, influencing the next generation (sometimes involving epigenetic switches, with how we are treated affecting which genes are activated). Where inequality has created a social condition where competition is the norm then you have to fight to get anything – and when everyone is a potential rival, you quickly learn not to trust other, perpetuating further competition and inequality. Yet for societies that are more equal, a different cycle emerges. When empathy and reciprocity are established as the norm, individuals come to depend on cooperation and consequently trust becomes the baseline. Trust breeds trust, and so it goes: two cycles, one negative, one virtuous – which we choose to follow is up to us.

All this can be summed up succinctly: the more inequality there is, the more superiority and inferiority there is; and with this, more status competition, its associated insecurity and the consumerism we try to use to address it. There is more social evaluation anxiety: the worrying about how we are seen and judged, how it affects our status and the impacts that this has on our self-esteem.

In the old naïve view inequality was only seen to matter if it created poverty. Now we see a new take: inequality matters because it brings out features of our psychology to do with dominance and subordination, superiority and inferiority – and these affect how we treat each other. If this all seems self evident, it’s because it affects each and everyone of us every single day. Social evaluative effect is as intense as it has ever been in human history: our frame of reference is now global, and shoehorned into a race to the top we can’t ever hope to compete in. We have been conditioned to see this as a private weakness, but – as Wilkinson pointed out in closing – part of overcoming this might be to see that we all have these fears.

June 6, 2014 at 12:53 am

Excellent post! We will be linking to this great content

on our website. Keep up the great writing.

October 15, 2014 at 8:18 am

Hello. Tomorrow is Blog Action Day on the theme of “Inequality”, and I plan to write a post and have been reading around, hence stumbled on you. Seems like if you just “re-post” you have a great contribution! http://blogactionday.org

October 15, 2014 at 10:43 am

Thanks – have checked it out 🙂

Pingback: #Inequality, Food, Climate: Thoughts on Blog Action Day | Kitchen Counter Culture